Mining is one of the biggest industries in Australia, with profits surging A$27.7bn in the second half of 2017, according to the Australian Financial Review.

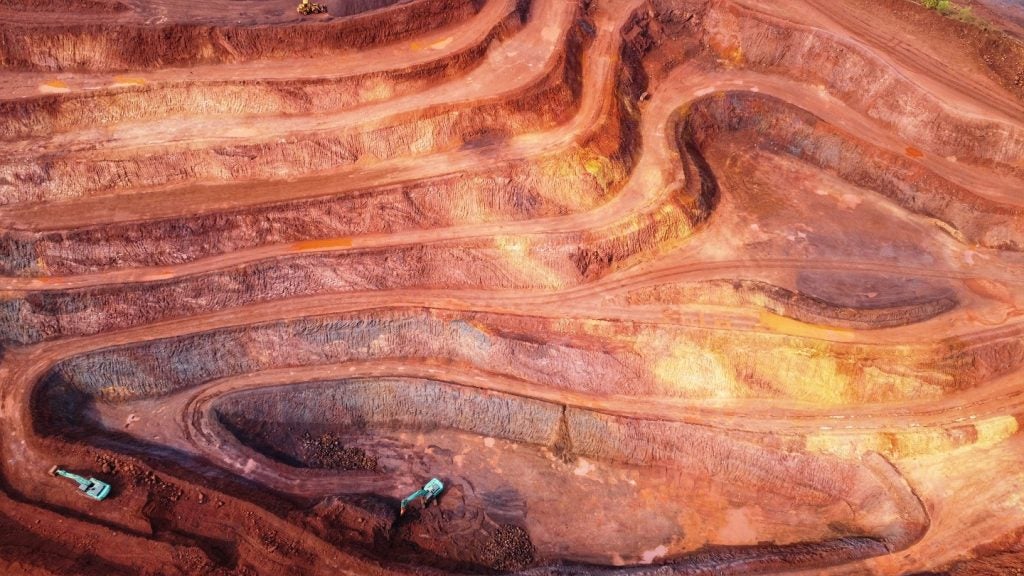

However, these profits often come at the cost of local environments, with topsoil removed, earth excavated and forests destroyed to make space for mining operations. The scale of mining projects often requires similarly extensive rehabilitation schemes, which incorporate new scientific developments and economic initiatives to help minimise the damage caused by mines, which are crucial for companies to obtain mining permits in the first place.

How well do you really know your competitors?

Access the most comprehensive Company Profiles on the market, powered by GlobalData. Save hours of research. Gain competitive edge.

Thank you!

Your download email will arrive shortly

Not ready to buy yet? Download a free sample

We are confident about the unique quality of our Company Profiles. However, we want you to make the most beneficial decision for your business, so we offer a free sample that you can download by submitting the below form

By GlobalData“Rehabilitation and mine closure are planned and considered across all stages of modern mine development and operation, from design to closure and rehabilitation is a critical component of a company’s environmental management,” said a spokesman for the Minerals Council of Australia (MCA).

Huntly and Willowdale: a comprehensive reforestation scheme

Alcoa’s Huntly and Willowdale mines in Western Australia produce 34 million tonnes (Mt) of bauxite per year, almost half of the 74Mt produced in Australia in 2011. The scale of the operations led to considerable deforestation since the mines began operation in 1963, and Alcoa has implemented an ambitious reforestation scheme to try to restore 100% of the plant species that were present in the Jarrah Forest before mining work began.

The company reached this target in 2001, as all of the plant species were reintroduced to the area, alongside new plants introduced to the region, leading to claims that Alcoa had achieved “101% of its goal”. The rehabilitation efforts have been spearheaded by the Marrinup Nursery at the mine, which provides a source of seeds and plants for the rehabilitation of mining land and enables scientists to conduct testing on new plant species that are being considered for introduction to the area. This is part of Alcoa’s aim to improve the biodiversity of the region and introduce plants that are more resilient and capable of surviving in Western Australia, which experiences an annual dry season.

The nursey is also equipped with a tissue culture laboratory to test a range of plant species, and is currently responsible for producing 50,000 plant cuttings a year.

Ginkgo mineral sands: progressive rehabilitation in arid conditions

Operations at the Cristal-owned Ginkgo mineral sands mine in New South Wales are still underway, but the project has been the recipient of an extensive progressive rehabilitation scheme, under which land is repurposed and reclaimed alongside mining operations.

One of the most significant forms of environmental damage at the project is the loss of topsoil and the resulting destruction of plant life on the surface of the soil. Cristal expects to strip 5.26m3 of topsoil from the land around the mine by 2021. Topsoil removed by mining operations has been replaced and combined with timber from trees originally cleared to make space for the mine, to create a series of protective microclimates. These microclimates encourage the growth of seeds and, in the long term, trees in the area.

Due to the irregular distribution of trees in the area and low average annual rainfall, seeds had to be carefully selected and collected from woodlands up to 500km from the mine site to provide the basis of the reforestation programme and ensure trees could grow in tough conditions.

The MCA commented that “one of the big challenges is integrating rehabilitation into the mine planning process; mine plans can change, which can impact on land that has already been rehabilitated.”

Cristal’s progressive scheme ensures rehabilitation takes place alongside, and can be adapted to fit, changing mining operations.

Woodcutters mine: returning land to its Indigenous owners

Work ceased at the Woodcutters lead-zinc operation in Australia’s Northern Territory in 1999 following 14 years of production. Newmont acquired the site when it bought Normandy Mining in 2002, and took on responsibility for the decommissioning and rehabilitation projects started by Normandy.

Newmont has completed two significant rehabilitation projects: filling in the mine’s pit and covering the land with native grass and tree species, which was completed in 2005; and transferring 480,000m3 of soil to the dam’s tailings sites to prevent harmful materials from seeping into local waterways. The land excavated to provide this soil will then be turned into a wetland, an option preferred by local indigenous groups.

Newmont has taken particular care to work with these local groups and plans to return the site to the ownership of the Kungarrakan and Warai people by 2020. The company worked alongside groups such as the Indigenous Consulting Group, which aims to promote social and economic development for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia, and Rusca Bros Services, a local mining and recruitment company owned and operated by indigenous groups, for the soil transfer project. Newmont has reported that Indigenous people made up 90% of the workforce for this project.

Wilkie Creek: land rehabilitation and the local economy

The Wilkie Creek mine in Queensland was acquired in 2002 by Peabody, the world’s largest private coal company, but production was stopped in December 2013 as the project was no longer economically viable. Following two failed attempts to sell the mine in 2016 and 2017, Peabody has worked on an extensive land rehabilitation project.

The company has rehabilitated 395 hectares of land since 2014, equivalent to nearly two-thirds of the land used for mining projects. Much of the new land has been given over to cattle farming, enabling the mine to continue to impact the local economy. Peabody spends over A$6m a year on rehabilitation, around A$2.7m of which is spent on equipment and services provided by Queensland-based companies.

The company has also set aside more than A$150m in security deposits to the New South Wales Government to fund the rehabilitation of the company’s mines in the state, funds described by the MCA as “a safeguard of last resort.”

“The provision of a security bond does not remove a company’s obligation to rehabilitate land,” said the council. “These funds are intended to cover the full cost of rehabilitating mine sites.”

Renison Bell: research-led solutions to acidic tailings

Australia’s largest operating tin mine is the Metals X-owned Renison Bell operation in Tasmania, which has an annual production of 7,000t and has produced around 23Mt since production began in 1968. The owners have focused on rehabilitating the mine’s tailings storage facilities after it was discovered that tailings were oxidising in storage, producing a dilute form of acid known as acid mine drainage, which seeped into the nearby Lake Pieman.

Metals X worked with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation to develop an oxygen-excluding material to cover the tailings facilities to prevent oxidation, as well as a slurry containing a tailings component known as cassiterite flotation tailings, which was spread over land polluted by the acid. From 2002 to 2006, sulphate levels in tailings runoff fell from 1,500 milligrams per litre to just 70, and remained at those levels until 2013.

The MCA said that research-led rehabilitation methods such as Metals-X’s are strengthening Australia’s commitment to land rehabilitation in the long term.

“We recognise that historic mining practices and absence of adequate regulation has resulted in abandoned mines that have not been appropriately rehabilitated,” said the MCA. “These mines can undermine public confidence in the ability of the modern industry to manage its long-term environmental impacts.

“The industry’s approach to mined land rehabilitation has improved significantly over past decades driven by sustained company investment in research to strengthen the science underpinning rehabilitation methods, evolving corporate values, community expectations and government regulation.”